Exploding the Business Case for an Alberta to BC pipeline

Also no need for a huge political fight between Premiers Eby and Smith

For the past decade, Alberta political leaders have promised that access to Asian markets will transform the province’s oil sector. The argument is familiar: if Canada can reach tidewater on the Pacific Coast, ultra-heavy sour crude from the oil sands will supposedly fetch higher prices from refiners in China and India. That dream has shaped political messaging, public debate, and tens of billions of dollars of public spending.

It is a compelling story. But compelling stories are not always grounded in economic reality. Once you examine real breakeven costs, real shipping costs, real refinery preferences, and real global demand trends, a different picture emerges — one in which Alberta’s crude becomes a marginal barrel in Asia, not a competitive one. And a picture in which the business case for a new West Coast export pipeline collapses.

This is ultimately a story about competitiveness, risk, and the danger of building multi-decade infrastructure on yesterday’s assumptions.

Alberta’s Cost Structure: The Hard Truth Behind Breakevens

Alberta’s oil sands producers have made notable efficiency gains over the past decade. As the industry matured, operators shifted from megaproject build-outs to optimization and disciplined operational management. In-situ producers improved steam-to-oil ratios through better reservoir modelling and solvent-assisted processes, while mining operators like Suncor and Syncrude reduced unit costs by improving maintenance planning, automating haul trucks, optimizing ore blends, and improving upgrader reliability.

These were not headline-grabbing breakthroughs. They were incremental improvements that compounded over time, enabling producers to extract more oil from the same infrastructure with fewer outages and better workforce productivity.

As a result, breakeven costs for existing (Brownfield) oil sands projects sit in the $40–$50 WTI range. That number contains three main components:

Operating costs: $20–$35 per barrel

Sustaining capital: at least $4–$8 per barrel

Shareholder returns: $5–$8 per barrel to meet dividend and buyback expectations

Some projects are lower, some higher, but this range reflects a defensible industry average.

On a pure production-cost basis, the oil sands can compete against many heavy-oil suppliers. Saudi Arabia and Iraq produce for under $10 per barrel, but their fiscal breakevens, the price they need to support their governments, often exceed those of Canadian producers. Meanwhile, Venezuela and Mexico face higher operating costs and chronic underinvestment.

In other words, the barrel itself is competitive. What isn’t competitive is getting that barrel to Asia.

Add $18 per Barrel of Shipping — and Alberta Becomes Marginal in Asia

Shipping diluted bitumen to China or India adds roughly $18 per barrel in transport costs — marine freight, insurance, and dockage fees. TMX’s Burnaby terminal can only load smaller tankers, increasing costs compared to the VLCCs used by rivals.

The arithmetic is simple:

$40–$50 breakeven

+$18 shipping

=$58–$68 per barrel landed (before quality penalties)

At those prices, Alberta’s crude is at the margin in Asia.

Asian refiners — among the most competitive in the world — have cheaper, easier-to-process options:

Saudi and Iraqi heavy

Brazilian and Guyanese medium blends

U.S. Gulf Coast light and medium barrels

Refiners don’t buy expensive barrels when cheaper, better-quality ones are available. Alberta’s crude enters Asia not as a premium product, but as the last barrel accepted.

Quality Penalties Compound the Disadvantage

Alberta’s diluted bitumen is:

ultra-heavy

extremely sour

high in metals and asphaltenes

low in valuable light ends

Only a subset of Asian refineries can process it efficiently — and those configurations are reserved for the most profitable heavy barrels, not the most expensive.

If it costs more to process Alberta’s crude and more to ship it, refiners simply buy something else.

Alberta’s Asia Dream Requires Believing in Rising Demand to 2050

Why, then, does Alberta insist on chasing Asian markets?

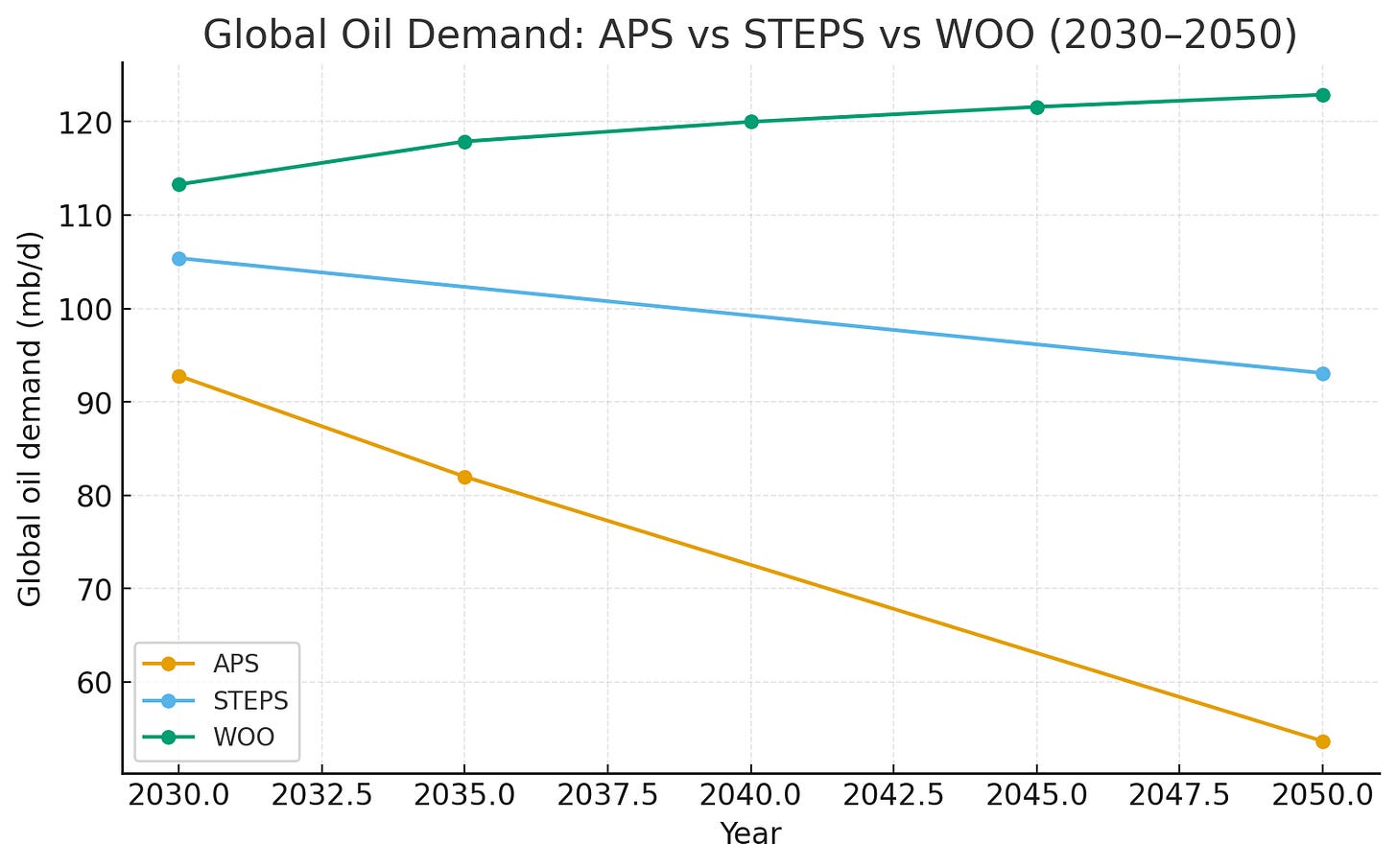

Because doing so requires believing in the OPEC or IEA Current Policies Scenario (CPS) view of the future: one where global oil demand grows from 103 million barrels per day today to roughly 120 million barrels per day by 2050.

In that world, high-cost barrels still clear the market. Prices average higher. Volatility is lower. And Alberta’s crude can find a place.

But that world depends on one assumption: oil demand keeps growing for 25 years. It neither plateaus nor declines — it grows. And that is not what current data or policy trends suggest.

The IEA’s APS Scenario — the Most Evidence-Based Outlook — Says the Opposite

The IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), which reflects firm government commitments, projects that:

oil demand peaks around 2030

then declines toward 55 million barrels per day by 2050

This is the scenario most consistent with observable trends:

EV adoption

electrification of freight

rapid efficiency gains

petrochemical feedstock substitution

changing consumer patterns

stronger climate policy

Under APS, oil demand doesn’t collapse — but it becomes progressively smaller and more volatile. High-cost barrels are squeezed out first.

There is no APS scenario in which Alberta becomes competitive in Asia.

There is no APS scenario in which Asian refiners choose the most expensive heavy barrel. And there is no APS scenario in which Alberta outcompetes Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Mexico, or Venezuela.

The Pipeline Thesis Collapses Under Demand Contraction

A new West Coast export pipeline requires believing in:

high long-term demand

sustained high prices

stable Asian appetite for Alberta’s heavy sour crude

new supply growth sufficient to fill the pipe

Under APS, all of those assumptions fail.

In a shrinking market, refiners become choosier. Heavy barrels face the steepest penalties. High-cost, long-distance suppliers lose market share. Pipeline economics worsen as throughput declines, tariffs rise, and netbacks fall — producing a slow-motion stranded asset.

Greenfield Costs Make the Business Case Even Worse

Even if demand were stable, Alberta cannot fill a one-million-barrel-per-day pipeline using brownfield expansions alone. The only way to generate that volume is through new Greenfield oil sands projects, and their economics are dramatically worse.

Capital Costs

New mines or SAGD projects require $10–$20 billion in upfront capital for 150,000–250,000 barrels/day of capacity:

$60,000–$90,000 per flowing barrel (mining)

$45,000–$70,000 per flowing barrel (SAGD)

Operating Costs

Greenfield OPEX is $5–$15 higher per barrel than at mature sites.

Breakevens

Brownfield: $40–$50

Greenfield: $55–$70

Landed in Asia

+$18 shipping

=$73–$88 per barrel landed

No Asian refiner chooses a $75–$88 landed-cost barrel when competitors deliver for $40–$50.

A pipeline justified by Asian demand requires barrels that won’t be competitive enough to be produced.

CER’s Modelling Shows Falling Production, Not Rising

The Canada Energy Regulator’s Energy Future 2023 report modelled long-term production under the Canada Net-zero scenario, which uses IEA APS prices:

$64 per barrel in 2030

$60 by 2050

Under those conditions:

Production peaks at 3.64 million b/d in 2030,

then declines to 2.30 million b/d by 2050 — a 30% drop.

Here is the key insight: All of that production is absorbed by existing U.S. markets.

None of it requires new tidewater access. None of it generates an extra 1 million barrels per day.

A declining industry cannot fill a new pipeline. A shrinking market does not require new export capacity. A U.S.-oriented supply chain does not magically become an Asian strategy. If APS-level prices prevail, Canada will not have enough oil to fill its existing pipelines, let alone build another.

Carbon Tracker Reaches the Same Conclusion

Carbon Tracker’s modelling, based on Rystad’s asset-level data and the IEA APS, finds:

Canadian oil sands sit on the wrong end of the cost curve

Greenfield projects are economically unviable under APS

Provincial oil and gas revenues could fall 80% in the 2030s

The only competitive market for oil sands crude is the United States

Once you add $15–$20 per barrel to ship to Asia, oil sands crude becomes a high-cost marginal barrel.

In Carbon Tracker’s APS modelling, the barrels Alberta wants to export to Asia do not exist because the market will not pay enough to justify producing them.

Marginal Barrels Don’t Justify Multi-Billion-Dollar Pipelines

When you put all the evidence together, the conclusion becomes unavoidable:

Alberta’s crude is competitive only in the U.S.

It becomes marginal the moment it must be shipped to Asia

APS-level demand eliminates the future volumes needed to fill a pipeline

Greenfield costs make new production uneconomic

CER and Carbon Tracker both model falling supply, not rising

The pipeline depends on OPEC-style demand growth that is unlikely to materialize

The Political Courage to Tell the Truth

Telling voters that Asia will pay a premium for Alberta’s oil is easy.

Telling them the opposite — that Asia won’t, and that Alberta’s barrel is drifting further toward the margin — is hard.

But responsible economic planning demands honesty. It demands acknowledging that a world of declining oil demand is a world of fierce competition, not expanding opportunity. It demands recognizing that a barrel costing ~$60 landed in Asia will not beat barrels delivered for $35–$45.

And it demands resisting the temptation to cling to comforting narratives instead of market realities.

The truth, supported by the arithmetic, is that Alberta’s ultra-heavy sour crude is a marginal barrel in Asia, and a pipeline to the Pacific makes no economic sense in a declining-demand world. The sooner we plan around reality, the stronger Canada’s economic future will be.

I will watch the video you put up again tomorrow, I was only able to half pay attention today. It is a shame (but understandable) the Rystad numbers can't be said. But I am skeptical many new developments would be SAGD vs solvent washes like N-solv. I also think it is very much possible to get those operating costs lower. I expect there will also be supply shocks in the future where prices spike, during which periods returns are higher without any changes to long-run operations

You keep staying that we are most competitive in the US with 60% of the heavy crude market. This seems very concentrated and impacted by even small drops in demand. I don't understand why you seem to believe the US Midwest will not see demand fall. I can understand why you question the economics, but I do think you are over estimating transportation prices. Also, what does Marginal barrel actually mean? That many refineries use a little?

Lastly; you keep repeating this "In a shrinking market, refiners become choosier. Heavy barrels face the steepest penalties" But that doesn't make it true. I'm happy to again list all the reasons I think it is not, but other than Historic Trends, which this distruptive environment upends, why do you believe it will remain true? At the same time, as demand fails, countries will not reinvest in exploration or drilling, and supply will be falling alongside - if not as quickly. But in this situation of increasing concentration of producers, I would expect a higher premium on stability and diversification of source. .

Net Zero has been abandoned by Carney and he and the oil patch are busily trying to spin away the sector decline, while actively blocking the coming renewables revolution.