A Modest Proposal for Expanding the Canadian Auto Sector, Especially EVs

Is Magna International's contract manufacturing facility in Graz, Austria a model for Ottawa's auto strategy?

Last fall, several interesting Magna International press releases landed in my inbox. The giant Canadian auto supplier has contracted to build electric vehicles (EVs) for two Chinese companies. In Graz, Austria, of all places. Why Austria? Because Magna has a huge plant there that specializes in contract manufacturing. It doesn’t have a similar facility in Canada. Maybe that presents a unique opportunity for Ottawa’s new auto sector strategy.

“Recognizing that the future of the automotive industry is electrified and connected, the Government of Canada is prioritizing the development of the full value chain for next‑generation vehicles,” according to the backgrounder for that strategy.

One way to do that is attract an existing automaker to build a gleaming greenfield plant. Thousands of jobs announced in a single press conference, complete with hard hats and flags. The full vertical stack, from stamping to final assembly, delivered in one heroic act of industrial faith. Not to mention future press conferences to highlight EV supply chain expansions.

Another way is represented by Magna’s factory in Austria. This model is gaining prominence as China’s automakers “localize production” in other countries, like Brazil and Thailand. The automaker retains control over the product, the brand, the intellectual property, and the route to market. The contract manufacturer owns and operates the plant, hires and manages the workforce, integrates the supplier base, and executes final vehicle assembly to the automaker’s specifications.

Risks are shared, not merged.

Contract manufacturing is a different business logic. Flexibility replaces permanence. Platforms (manufacturing system designed to support multiple customers, products, and futures) replace monuments (one-off, capital-intensive factories built for a single company). Contract manufacturing absorbs uncertainty that “prestige projects” cannot.

This approach seems to be consistent with the auto strategy and Canada’s new agreement with China. The “strategic plan” will “will look to drive new Chinese joint venture investment in Canada.” There are no details about what those joint ventures might look like. Contract manufacturing seems, at least, to be consistent with the intent of the strategy.

:Let’s explore that idea.

The Graz Facility as an Industrial Service

Magna’s Graz plant in Austria is one of the clearest examples in the global auto industry of a flexible contract vehicle assembly facility rather than a traditional, single-brand factory. Unlike a dedicated OEM plant built for one automaker’s products and volume forecasts, the Graz facility is designed to build vehicles for multiple customers under contract, adapting to different platforms, powertrains and market requirements without long shutdowns or massive retooling.

Automakers that partner with Magna—including Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Toyota, Jaguar Land Rover—for production at Graz bring their vehicle designs, engineering specifications and quality standards; Magna supplies the production systems, workforce, supply-chain integration and the disciplined execution needed to turn those designs into serially assembled vehicles.

This means the plant can shift between products more easily, accommodating internal combustion, hybrid and electric platforms on shared lines and integrating varied supplier modules as needed.

What makes Graz a flexible manufacturing system is its ability to absorb uncertainty and change: production lines are modular, work processes are standardized across models, and scheduling can be reconfigured as contracts evolve. Rather than anchoring a legacy brand in a fixed footprint, it acts as a neutral, multi-tenant industrial hub that multiple automakers can plug into, shortening time to market and spreading risk across a broader set of production commitments.

Contract manufacturing lowers the threshold for market entry. It shortens the time to production. It spreads risk across multiple customers rather than concentrating it in a single corporate bet. It allows governments to capture jobs and learning without underwriting entire balance sheets.

Most importantly, it builds industrial capability without demanding certainty from the future.

Magna International one of the world’s most capable automotive contract manufacturers

Founded by Canadian icon Frank Stronach, managed for a time by his one-time politician daughter Belinda, the company is headquartered in Aurora, Ontario.

Magna is one of Canada’s largest companies by revenue, generating roughly C$56–59 billion in 2025 across its global network of engineering, supply and assembly activities. The corporation employs about 164,000 people worldwide, with a significant share in Canada. It operates dozens of facilities that produce vehicle systems, modules, electrification components, and advanced assemblies, and contribute to complete vehicle programs as a contract manufacturer.

That includes a wide range of EV components.

Which Horse Should Canada Ride in the EV Race?

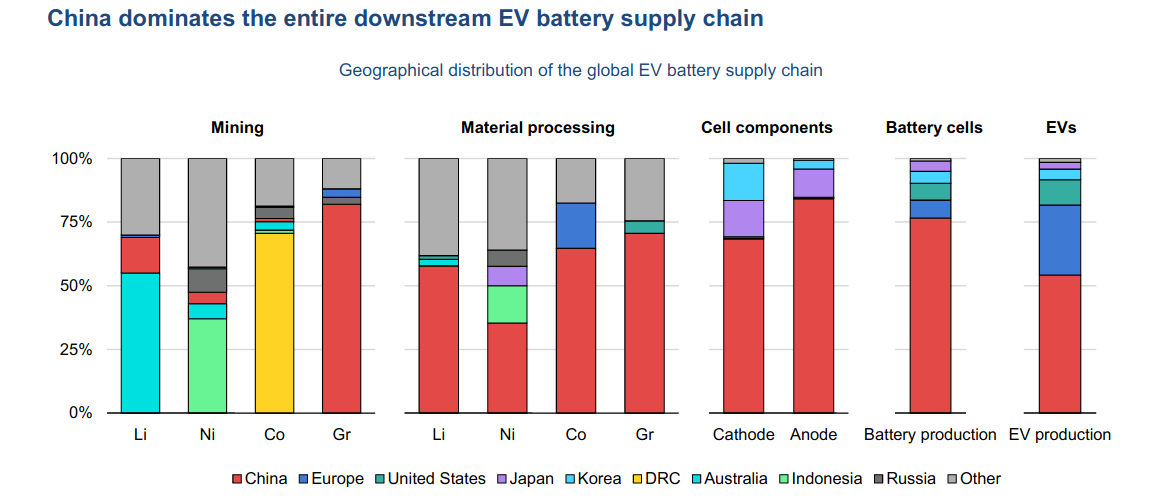

The Carney government wants Canada to be a global leader in EV manufacturing. As of this moment, Ottawa’s eyes are far bigger than its stomach. China dominates the field. In 2024 alone, Chinese manufacturers produced about 12.4 million electric vehicles, accounting for more than 70 per cent of global EV output. China controls between 70 per cent and 90 per cent of the global EV supply chain.

By comparison, the deeply integrated auto manufacturing system of the United States, Canada, and Mexico controls single digit percentages of EV production and supply chains. GM, Ford, and Stellantis have trumpeted their EV efforts for years, but recent announcements show how miserably they’ve failed. The Big Three, as they used to be called, last year took over US$50 billion of write downs on their EV investments. All have scaled back EV ambitions.

They are a classic example of Harvard professor Clay Christen’s theory of disruptive innovation. The incumbents—the legacy OEMs—understood that EVs are the future, but they depended on ICE vehicles like trucks and SUVs for profitability. Pivoting from combustion technology to electric technology has proven to be a daunting challenge.

Japanese OEMs with Canadian plants—Toyota and Honda—have taken the opposite approach. Hybrids have been their focus. They are only now tentatively dipping a toe in the full-EV waters. They are laggards, not innovators like the Chinese companies.

In fact, both groups of OEMs are laggards. The Big Three are ambitious but failures, while the Japanese are cautious but far behind.

Which horse, then, should Canada ride in the madcap race to survive in the deeply disrupted global auto industry?

Magna’s Graz Plant as the Model for Canada’s New Auto Strategy

Magna already operates the kind of industrial service model Ottawa says it wants, even if policy has never fully caught up to it. It is not a speculative entrant or a subsidy-seeking newcomer. It is a Canadian-headquartered company with decades of experience acting as a neutral, brand-independent builder inside the global auto industry.

Neutrality is strength. It is the point.

As the EV transition fragments manufacturing into platforms, modules, and services rather than monolithic plants, Canada needs an anchor that understands this reality. Magna does. It brings industrial credibility, balance-sheet strength, global customer relationships, and a proven ability to translate policy ambition into shop-floor execution.

If Canada wants a national champion that builds durable and flexible manufacturing capacity rather than one-off monuments, Magna is the obvious place to start.

Does Canada have the strategic smarts to embrace a different business model?

How Canada Defines Industrial Success

Canada does support manufacturing that falls short of full vehicle assembly. Governments fund battery materials, cathode plants, module assembly, power electronics, and tier-one auto parts. These investments are real. They matter.

But they are also framed as supporting acts.

In Canada’s industrial imagination, success still culminates in the full OEM plant. That is the prize. That is the validation. That is what anchors subsidy negotiations, political narratives, and long-term strategy. Everything else is described as “building the ecosystem,” a phrase that quietly acknowledges importance while denying primacy.

This hierarchy matters.

Because contract vehicle manufacturing does not fit cleanly into it. It is neither a branded OEM win nor a neat upstream input.

It sits in between. And because it sits in between, it is rarely pursued deliberately, designed for explicitly, or rewarded politically.

Why Vertical Integration Became the Default

The preference for full OEM plants did not emerge by accident. It is rooted in an earlier era of industrial policy, when scale was everything and certainty was assumed. If a company was willing to invest billions in a single location, governments could justify building long-term policy and infrastructure around it.

That logic worked when product cycles were slow, capital was cheap, and geopolitical risk was background noise.

It works less well now.

The EV transition is unfolding under conditions of persistent uncertainty. Markets are volatile. Demand curves are uneven. Capital costs have risen. Politics intrude constantly. New entrants do not know how fast they will scale. Legacy automakers do not know how quickly their customers will switch.

Betting everything on a single, vertically integrated facility is no longer conservative. It is exposed.

Why This Should Be Obvious to Canada

Canada should recognize this instinctively. It aligns with how the country has historically succeeded. Canada did not become an industrial economy by insisting on brand ownership. It became indispensable inside other people’s supply chains. Reliable. Skilled. Trusted. Hard to replace.

The irony is that Canada already has the anchor firm capable, Magna International, of making this model work domestically.

Its leadership, engineering culture, and manufacturing DNA are deeply Canadian. It operates dozens of plants across the province. It is already investing hundreds of millions of dollars in EV-adjacent manufacturing, from battery enclosures to advanced vehicle structures. The labour force exists. The supplier ecosystem exists. The logistics corridors exist. The institutional knowledge exists.

What does not exist is a Canadian equivalent of Graz. There is no standing, brand-neutral, complete-vehicle contract manufacturing platform in Canada that automakers anywhere in the world can plug into.

Not because it cannot be built, but because Canada has never treated this model as a strategic objective.

Industrial policy has been designed around anchor tenants and flagship plants. Contract manufacturing does not deliver that kind of clarity. It is modular. Incremental. Multi-tenant. It scales quietly. It accumulates value over time rather than announcing it all at once.

That makes it politically underwhelming. As a result, it falls through the cracks.

Why the China Debate Distracts

Once this is understood, the fixation on China becomes a distraction. Yes, Chinese EV manufacturers are using contract manufacturing in Europe to localize production and navigate trade barriers. That is true. But it is not the core insight.

The insight is that the model works regardless of the flag on the hood.

A Canadian Magna platform could assemble EVs for Indian automakers seeking North American entry without U.S. political exposure. It could support Japanese firms making a cautious, staged pivot to electric. It could serve European niche manufacturers’ testing demand. It could give North American EV startups a way to build vehicles without incinerating capital.

The opportunity is structural, not geopolitical.

Beyond Passenger Cars

This logic becomes even stronger once the focus moves beyond light-duty consumer vehicles.

Medium-duty trucks. Work vans. Utility fleets. Mining and forestry vehicles. Specialty platforms designed for cold climates and long duty cycles. These are not markets that reward massive, single-model plants. They reward flexibility, customization, and manufacturing discipline.

They reward exactly the capabilities contract manufacturing is designed to provide.

Canada’s geography, climate, and resource economy make it a natural proving ground for this kind of vehicle innovation. Yet policy attention remains fixed on passenger vehicles—the narrowest, most capital-intensive segment of the market.

The Cost of Treating Platforms as Secondary

By treating contract manufacturing as success in its own right, Canada concentrates risk, stretches timelines, and constrains its industrial choices, leaving less room for new entrants, experimentation, or learning without political fallout.

When trade barriers rise or global strategies shift, there is no domestic platform ready to adapt. Protection replaces participation.

This is often justified as realism. In practice, it is fragility.

What a Platform Strategy Would Say

A Canadian contract-manufacturing strategy would sit alongside vertically integrated plants, catching opportunities they cannot or will not pursue. It would act as a bridge for companies not ready to commit and as a home for vehicles that do not fit mass-production logic.

Most of all, it would signal that Canada understands how the EV transition is actually unfolding. Not as a single race to the biggest factory, but as a fragmented, uncertain reconfiguration of how vehicles are designed, built, and brought to market.

Magna’s Austrian plant shows what that future looks like. Canada’s failure to replicate it at home is not a failure of capacity, but of imagination.

Markham’s note: Automotive manufacturing is not my beat. As much work as I did to get this essay right, it’s likely I also made mistakes. Happy for those mistakes to be pointed out by actual auto experts. But this essay also illustrates a strength of Energi Media’s journalism. By focusing half of our reporting on global energy and technology news, we can spot trends and connect dots that other Canadian media miss. That’s what I tried to do here. And may do again in future essays and videos.

You may also want to take a look at the St. Thomas battery plant. My understanding is, like the Austrian MAGNA plant, it's designed to allow assembly lines to switch between a variety of battery chemistries and designs.

I feel somewhat conflicted about automotive manufacturing. It is, to some degree a dwindling sector, though obviously critical to southern Ontario in particular.

In the long term, we need to move away from such ubiquitous use of private vehicles and embrace more public transportation.

But in the meantime, GM are pulling production of a commercial electric vehicle from a plant in Ingersoll. It is a relatively modern plant, which could be repurposed to a Canadian built EV. In addition, its proximity to the St Thomas battery plant mentioned by Neolithic could be beneficial.